By Norman Robespierre

YANGON - A recent flurry of high-level contacts between North Korea and Myanmar raises new nuclear proliferation concerns between the two pariah states, one of which already possesses nuclear-weapon capabilities and the other possibly aspiring.

At least three delegations led by flag-level officers from Myanmar's army have traveled to Pyongyang in the past three months, hot on the heels of the two sides' re-establishment last year of formal diplomatic relations. According to a source familiar with the travel itineraries of Myanmar officials, Brigadier General Aung Thein Lin visited North Korea in mid-September.

Before that, other Myanmar military delegations visited North Korea, including a group headed in August by Lieutenant General Tin Aye, chief of the Office of Chief Defense Industries, and another led in July by Lieutenant General Myint Hlaing, the chief of Air Defence.

The rapid-fire visits have gone beyond goodwill gestures and the normal diplomatic niceties of re-establishing ties. Rather, the personalities involved in the visits indicate that Myanmar is not only seeking weapons procurements, but also probable cooperation in establishing air defense weaponry, missiles, rockets or artillery production facilities.

The secretive visits are believed to entail a Myanmar quest for tunneling technology and possible assistance in developing its nascent nuclear program. Tin Aye and Myint Hlaing, by virtue of their positions as lieutenant generals, are logical choices to head official delegations in search of weapons technology for Myanmar's military, while Brigadier General Aung Thein Lin, current mayor of Yangon and chairman of the city's development committee, was formerly deputy minister of Industry-2, responsible for all industrial development in the country.

Prior to 1998, the minister of Industry-2 also served as the chairman of the Myanmar Atomic Energy Committee. This came to an end when Myanmar's Atomic Energy Act of 1998 designated the Ministry of Science and Technology as the lead government agency for its aspirant nuclear program. However, the Ministry of Industry-2, by virtue of its responsibilities for construction of industrial facilities and the provision of equipment, continues to play a key supporting role in Myanmar's nuclear program.

Myanmar's stagnant nuclear program was revitalized shortly after Pakistan's first detonation of nuclear weapons in May 1998. Senior general and junta leader Than Shwe signed the Atomic Energy Law on June 8, 1998, and the timing of the legislation so soon after Pakistan's entry into the nuclear club did little to assuage international concerns about Myanmar's nuclear intentions. Some analysts believe the regime may eventually seek nuclear weapons for the dual purpose of international prestige and strategic deterrence.

Myanmar's civilian-use nuclear ambitions made global headlines in early 2001, when Russia's Atomic Energy Committee indicated it was planning to build a research reactor in the country. The following year, Myanmar's deputy foreign minister, Khin Maung Win, publicly announced the regime's decision to build a nuclear research reactor, citing the country's difficulty in importing radio-isotopes and the need for modern technology as reasons for the move.

The country reportedly sent hundreds of soldiers for nuclear training in Russia that same year and the reactor was scheduled for delivery in 2003. However, the program was shelved due to financial difficulties and a formal contract for the reactor, under which Russia agreed to build a nuclear research center along with a 10 megawatt reactor, was not signed until May 2007.

The reactor will be fueled with non-weapons grade enriched uranium-235 and it will operate under the purview of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations' nuclear watchdog. The reactor itself would be ill-suited for weapons development. However, the training activities associated with it would provide the basic knowledge required as a foundation for any nuclear weapons development program outside of the research center.

Constrained reaction

The United States' reaction to Myanmar's nuclear developments has been somewhat constrained, despite the George W Bush administration referring to the military-run country as an "outpost of tyranny".

After Myanmar's 2002 confirmation of its intent to build the reactor, the US warned the country of its obligations as a signatory to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). After the contract was formally announced in May 2007, the US State Department expressed concerns about the country's lack of adequate safety standards and the potential for proliferation.

The warming and growing rapport between Myanmar and North Korea will likely further heighten Washington's proliferation concerns. Myanmar broke off diplomatic relations with Pyongyang in 1983, after North Korean agents bombed the Martyr's mausoleum in Yangon in an attempt to assassinate the visiting South Korean president, Chun Doo-hwan.

The explosion killed more than 20 people, mostly South Korean officials, including the deputy prime minister and the foreign minister, and the South Korean ambassador to Myanmar. Four Myanmar nationals perished and dozens more were wounded in the blast. Myanmar severed ties with North Korea after an investigation revealed the three agents responsible for planting the bomb spent the night at a North Korean diplomat's house before setting out on their mission.

However, common interests have brought the two secretive nations back together. The famine in North Korea in the late 1990s and Myanmar's military expansion ambitions, including a drive for self-sufficiency in production, have fostered recent trade flows. While Myanmar has the agricultural surplus to ease North Korean hunger, Pyongyang possesses the weapons and technological know-how needed to boost Yangon's military might. There is also speculation Myanmar might provide uranium, mined in remote and difficult-to-monitor areas, to North Korea.

As testament to Pyongyang's willingness to supply weapons to the military regime, more North Korean ship visits have been noted at Thilawa port in Yangon, one of the country's primary receipt points for military cargo. During one of these visits in May 2007, two Myanmar nationals working for Japan's News Network were detained outside Yangon while covering a suspected arms delivery by a North Korean vessel.

Growing bilateral trade has helped to heal old diplomatic wounds and eventually led to a joint communique re-establishing diplomatic relations in April 2007. The emerging relationship is also a natural outgrowth of the ostracism each faces in the international arena, including the economic sanctions imposed and maintained against them by the West.

While it is possible the recent visits are related to Myanmar's nascent nuclear program, the evidence is far from conclusive. Nevertheless, Myanmar has undoubtedly taken notice of the respect that is accorded to North Korea on the world stage because of its nuclear weapon status. Unlike North Korea, Myanmar is a signatory to the NPT.

Myanmar has publicly stated it seeks nuclear technology only for peaceful purposes, such as developing radio-isotopes for agricultural use and medical research. Yet two well-placed sources told this reporter that North Korean and Iranian technicians were already advising Myanmar on a possible secret nuclear effort, running in parallel to the aboveboard Russia-supported program. Asia Times Online could not independently confirm the claim.

The lack of participation by Myanmar's Ministry of Science and Technology in the recent trips to Pyongyang would seem to indicate that nuclear developments were probably not the primary focus of the high-level meetings. The regime is also known to be interested in North Korea's tunneling technology (see Myanmar and North Korea share a tunnel vision, Asia Times Online, July 19, 2006) in line with the ruling junta's siege mentality and apparent fears of a possible US-led pre-emptive military attack.

The junta and others have no doubt noted the extraordinary problems tunneling and cave complexes have caused US forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, not to mention the success North Korea has enjoyed in hiding underground its nuclear facilities. Bunkers are rumored to underlie several buildings at Naypyidaw, where the regime abruptly moved the national capital in 2005. The ongoing construction of a second capital, for the hot season, at Yadanapon, is also believed to have tunnels and bunkers integrated into its layout.

Whether the visits are related to arms procurement, military industrial development, tunneling technology or nuclear exchange, they foreshadow a potentially dangerous trend for Myanmar's non-nuclear Southeast Asian neighbors and their Western allies, including the US.

As the true nature of the budding bilateral relationship comes into closer view, the risk is rising that Pyongyang and Yangon are conspiring to create a security quandary in Southeast Asia akin to the one now vexing the US and its allies on the Korean Peninsula.

Myanmar and North Korea share a tunnel vision

BANGKOK - Under perceived threats from the US, Myanmar and North Korea are strengthening their strategic ties in a military-to-military exchange that includes weapons sales, technology transfer and underground tunneling expertise.

Myanmar's ruling State Peace and Development Council last year abruptly moved the country's capital to a secluded location near the mountainous town of Pyinmana, 400 kilometers north of Yangon, where the SPDC has built an entirely new city in the jungle.

Ordinary citizens do not have the right to enter the new capital, Nay Pyi Daw, which is populated entirely by soldiers and government officials. During the March 27 Armed Forces Day

celebrations held there, civilian diplomats were barred from attending and only foreign defense attaches were invited.

North Koreans, however, are allowed unfettered access to the secluded new capital. Last month, Asian intelligence agencies intercepted a message from Nay Pyi Daw confirming the arrival of a group of North Korean tunneling experts at the site. Nay Pyi Daw is in the foothills of Myanmar's eastern mountains, and it has long been suspected by Yangon-based diplomats that the most sensitive military installations in the new capital would be relocated underground.

The SPDC's apparent fear of a preemptive US invasion or being the target of US air strikes was seen as a major motivation behind the junta's decision to move the capital to what they perceive to be a safer mountainous location. The administration of US President George W Bush has publicly lumped Myanmar with what it considers rogue regimes, and US officials have recently referred to Myanmar as an "outpost of tyranny".

That perceived threat has drawn Myanmar and North Korea closer together in recent months. One key component of those growing strategic ties is North Korea's expertise in tunneling. Pyongyang is known to have dug extensive tunnels under the demarcation line with South Korea as part of contingency invasion plans.

Most of Pyongyang's own defense industries, including its chemical- and biological-weapons programs, and many other military installations are underground. This includes known factories at Ganggye and Sakchu, where thousands of technicians and workers labor in a maze of tunnels dug into and under mountains. The United States suspects there could be hundreds of underground military-oriented sites scattered across North Korea.

Curious connection

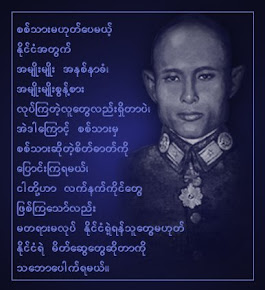

Myanmar's curious North Korean connection has been the subject of much strategic speculation ever since it was first disclosed in the Far Eastern Economic Review in 2003. Preliminary reports were met with skepticism because Myanmar (then known as Burma) had severed diplomatic relations with North Korea in 1983 after three secret agents planted a bomb at Yangon's Martyrs' Mausoleum and killed 18 visiting South Korean officials, including then-deputy prime minister So Suk-chun and three other government ministers.

One of the North Korean agents, Kim Chi-o, was killed by Burmese security forces in the ensuing gun battle, while the others, Zin Mo and Kang Min-chul, were captured. Two years later, Zin, a North Korean army major, was hanged at Insein jail on the outskirts of the then-capital Rangoon (Yangon), while Kang was spared because he cooperated with the prosecution. Kang still languishes in Insein, but is reported to be staying in the so-called "Villa Wing" - a small private house with a tiny garden surrounded by high barbed-wire fences.

Reports about renewed ties between the two pariah nations gradually began to emerge - and it seems that Kang, unwittingly, was the reason the relationship was restored. In the early 1990s, secret meetings were held in Bangkok between North Korea's and Myanmar's ambassadors to Thailand. Pyongyang negotiated for Myanmar to extradite Kang, presumably because it wanted to punish him for betraying the "fatherland".

But the two sides soon discovered that they actually had much more in common than their unfortunate history. Both authoritarian countries were coming under unprecedented international condemnation, especially by the US. Moreover, Myanmar needed more military hardware to battle ethnic insurgent groups and North Korea was willing to accept barter deals for the armaments, an arrangement that suited the cash-strapped generals in Yangon.

The bilateral relationship has reportedly intensified in recent years as both countries come under heavy US pressure.

"They have both drawn their wagons into a circle ready to defend themselves," a Bangkok-based Western diplomat said in reference to Myanmar-North Korean ties, adding that Myanmar's generals "admire the North Koreans for standing up to the United States and wish they could do the same. But they haven't got the same bargaining power as the North Koreans."

Recent regional media reports about North Korea possibly providing nuclear know-how to Myanmar's generals are probably off the mark - at least for now. That said, North Korea has definitely been an important source of military hardware for Myanmar. According to Myanmar expert Andrew Selth, of Australia, the state in late 1998 purchased between 12 and 16 130-millimeter M-46 field guns from North Korea.

"While based on a 1950s Russian design, these weapons were battle-tested and reliable," Selth stated in "Myanmar's North Korean Gambit: A Challenge to Regional Security?" - a working paper he published with the Australian National University in 2004. "They significantly increased Myanmar's long-range artillery capabilities, which were then very weak."

Secret visits

According to South Korean intelligence sources, a delegation from Myanmar made a secret visit to Pyongyang in November 2000, where the two sides held talks with high-ranking officials of North Korea's Ministry of the People's Armed Forces. In June 2001, a high-level North Korean delegation led by Vice Foreign Minister Park Kil-yon paid a return visit to Yangon, where it met Myanmar's Deputy Defense Minister Khin Maung Win and reportedly discussed defense-industry cooperation.

The two sides reportedly did not discuss the reopening of official ties, still severed since the 1983 bombing incident. The cooperation has instead been kept low-key and purposefully not officially announced.

"It's a marriage of convenience," said an Asian diplomat who is tracking the expanding ties. "They share common interests and a common mindset. But [Myanmar] doesn't want to be seen as having forgiven North Korea for the [Yangon] bombing, or to antagonize South Korea, which has become an important trade partner."

North Korea and Myanmar are apparently only pursuing conventional arms sales and technology transfers, rather than high-tech weapons sales such as long-range missiles. To date, the most advanced weaponry that North Korea has delivered, or may be considering delivering, are surface-to-surface missiles (SSMs) for Myanmar's naval vessels. Myanmar currently has six Houxin guided-missile patrol boats, which were bought from China in the mid-1990s, according to Selth.

Based at Myanmar's main naval facility at Monkey Point in Yangon, each vessel is armed with four C-801 "Eagle Strike" anti-ship cruise missiles. Selth speculates that similar SSMs will be mounted on the three new corvettes that have recently been built at Yangon's Sinmalaik shipyard, or on to the navy's four new Myanmar-class patrol boats, which have likewise recently been built in local shipyards.

In July 2003, between 15 and 20 North Korean technicians were seen by intelligence sources at Monkey Point and later at a secluded Defense Ministry guesthouse in a northern suburb of the then-capital. North Korean technicians have since been spotted near the central Myanmar town of Natmauk - which led to the assumption they were involved in Myanmar's nuclear program because of its proximity to the site where Russia had planned to build a nuclear research reactor starting in 2000.

There is no evidence to indicate that Russia ever delivered the reactor, however. Myanmar's cash-strapped generals reportedly could not afford the ticket price, and unlike North Korea, Russia was not willing to accept the barter deal Myanmar had proposed. Nevertheless, several hundred Myanmar residents have gone to Russia for training in nuclear technology over the past five years, a strong suggestion that Myanmar has not entirely abandoned its nuclear ambitions.

The North Koreans now situated in central Myanmar are most likely there to help the SPDC protect its military hardware and other sensitive material from perceived US threats. In 2003, Myanmar's generals built a massive bunker near the central town of Taungdwingyi with North Korean assistance. The recent arrival of North Korean tunneling experts at Nay Pyi Daw lends credence to the suggestion that they are construction engineers with expertise in tunneling rather than nuclear physicists.

Still, the regional strategic implications of a North Korea-Myanmar defense relationship are similar. Rather than making Myanmar more secure and cash-strapped North Korea richer, news of the two sides growing strategic ties will likely lead to further international condemnation of both regimes.

Furthermore, Myanmar is a member to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and fellow members such as Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia are not likely to accept passively any sort of North Korean military presence within the geographical bloc. There have recently been calls to expel Myanmar from ASEAN for its abysmal human-rights record and lack of progress toward democracy.

By forging an alliance with Pyongyang, according to Selth, Myanmar's generals may in fact be encouraging the very development that it fears the most: active outside intervention in what they consider to be their "internal affairs".

.

.

.

.

.

October 4, 2008

Nuclear bond for North Korea and Myanmar

ဘယ္က႑ကလည္းဆိုေတာ့....

အၾကားအျမင္

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment