By Aung Zaw (Irrawaddy English) (Copy from Irrawaddy English Website)

For a while, the Burmese junta looked like it might be ready to meet the West halfway. The ouster of the regime’s spy chief ended all that

IN early 2000, Maj Aung Lynn Htut began his new assignment as the deputy chief of the Burmese embassy in Washington, DC, with a mission to improve ties with the incoming administration of President George W Bush.It was not his first time in the US capital. In 1987, the graduate of the elite Defense Services Academy spent three months in Washington receiving training from the CIA.

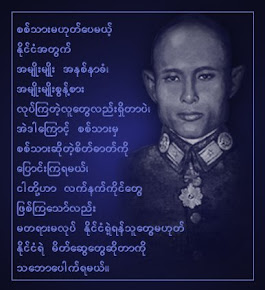

When he returned to the US in 2000, Aung Lynn Htut served as an officer in the counterintelligence department of the Office of the Chief of Military Intelligence (OCMI). His boss was Lt-Gen Khin Nyunt, secretary 1 of the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) and head of the junta’s powerful intelligence apparatus.

Khin Nyunt was also the architect of a series of ceasefire agreements with domestic insurgent groups that had strengthened the regime’s hold on power over the course of the preceding decade.

Khin Nyunt was also the architect of a series of ceasefire agreements with domestic insurgent groups that had strengthened the regime’s hold on power over the course of the preceding decade.

By the time Bush took office, Khin Nyunt appeared to believe that a détente with the junta’s staunchest international critic was also possible, according to Aung Lynn Htut.

“We waited until Bush came to power and then we started lobbying in DC,” said the former major.

In an extensive interview with The Irrawaddy, Aung Lynn Htut provided an inside look at this pivotal time in recent Burmese history, when the ruling regime seemed to be ready to turn a new page in its relations with the West.

As he revealed, however, it was also a period of intensifying rivalries within the junta.

Before Khin Nyunt could begin his experiment in reshaping ties with the US and other Western countries, he had to get a green light from the SPDC’s top leader, Snr-Gen Than Shwe.

As the strongman who called all the shots, Than Shwe was an inveterate hardliner who did not always take kindly to Khin Nyunt’s conciliatory overtures. But the intelligence chief’s success in sidelining former insurgents had allowed the regime to focus on its war of attrition against democratic forces; so, in a nod to Khin Nyunt’s proven ability to neutralize opponents through guile, Than Shwe gave him the go-ahead to work his magic on Washington.

Aung Lynn Htut’s assignment to Washington was one of the first tentative steps towards ending the regime’s isolation from governments it had long regarded as hostile.

Another part of the charm offensive was the launch of a colorful English-language newspaper, The Myanmar Times, which would present a more sophisticated image of the regime than the stodgy, Stalinistic fare offered by the state-run press.

As a further step, the regime hired DCI Group, a Washington-based lobbying firm, in 2002. The firm was paid US $348,000 to represent the junta, which had been strongly condemned by the US State Department for its human rights record. US Justice Department lobbying records show that DCI worked to “begin a dialogue of political reconciliation” with the regime.

The firm led a PR campaign to burnish the junta’s image, drafting releases praising Burma’s efforts to curb the drug trade and denouncing claims that the regime had used rape as a weapon in its military campaigns against ethnic insurgents.

By this time, the regime was becoming genuinely concerned that Bush’s policy on Burma was getting tougher. “We thought we had to counter it,” said Aung Lynn Htut.

He and his senior officers gathered information about who they could approach to ask for help. Khin Nyunt’s office started to reach out to Burma scholars who were sympathetic to the regime and who disagreed with the US government’s sanctions policy. Disgruntled prominent dissidents were also approached in a bid to persuade them to switch sides.

The regime also invited senior UN officials to come to Burma.Joseph Verner Reed, the UN undersecretary and special adviser to former UN chief Kofi Annan and now to Ban Ki-moon, arrived in Rangoon to attend an event marking United Nations Day in 2002. The high-ranking UN official was known to be close to some senior officers of the Burmese regime. Interestingly, he was listed on the board of the U Thant Institute in New York.

U Thant, a Burmese, was the UN secretary-general from 1961 to 1971.

In a speech to commemorate the founding of the UN, Khin Nyunt said that Burma had always considered the world body to be of fundamental importance for the preservation of international peace and security and for the promotion of the economic and social development of mankind.

“I wish to express our sincere appreciation and thanks to the United Nations and to the Honorable Under Secretary General Mr Joseph Verner Reed in particular for making this possible,” Khin Nyunt said in his speech, praising his special guest for attending.

But why did Khin Nyunt approach Reed in the first place?

“We gathered information that he didn’t like Aung San Suu Kyi,” Aung Lynn Htut, who acted as a liaison officer between Reed’s office and Khin Nyunt’s, said with a laugh.

In Washington, Burmese intelligence officers knew that it wouldn’t be so easy to find a sympathetic ear. They were up against US-based campaign groups and exiled Burmese activists who had considerable influence in forming US policy on Burma. They realized that it would not be easy to convince State Department officials, let alone Congress and the White House, that the regime was not as reprehensible as it had been portrayed.

Reports of forced labor, child soldiers and systematic rape committed by Burmese troops were thorny issues, and Khin Nyunt and his senior officers who handled foreign affairs realized that it would be an uphill battle.

Nevertheless, Khin Nyunt’s intelligence unit managed to reach a few US State Department officials with its message, including Matthew Daley, then head of the Southeast Asia Department. Daley once said that the US sanctions policy on Burma had failed and was not moving the country in the right direction.

Then, in May 2002, the regime took a bold step by releasing Suu Kyi. The Nobel Peace Prize winner was allowed to go on political organizing trips to the countryside. In return, she agreed to inspect the regime’s development projects.

That same month, despite a visa ban and active US sanctions, senior intelligence officer Maj-Gen Kyaw Thein was given a visa to enter the US to brief some senior government officials on the Burmese regime’s efforts to eradicate illicit opium production.

Meanwhile, as Suu Kyi began to travel around the countryside meeting her supporters, intelligence officers were engaging in behind-the-scenes negotiations with the opposition leader. Maj-Gen Kyaw Win, deputy head of OCMI, his deputy, Brig-Gen Than Htun, and Minister of Home Affairs Col Tin Hlaing were involved in the talks with Suu Kyi.

News of this “secret dialogue” was leaked to then UN Special Envoy Razali Ismail by Foreign Minister Win Aung, a loyal follower of Khin Nyunt. Razali, who played no part in facilitating this dialogue, released this information to the world, which welcomed the first signs of political progress to come out of the country in many years.

The “kinder and gentler” image of the junta was further enhanced by The Myanmar Times, which faithfully propagated the regime’s agenda. The newspaper gave extensive coverage to the regime’s fight against HIV/AIDS and its increased cooperation with the UN, and even highlighted a visit to Burma by the family of U Thant as evidence of a changing political climate.

As all of these developments were unfolding, Khin Nyunt gave briefings to Than Shwe to attempt to persuade the junta’s supreme commander to open up more space for international agencies such as the International Labor Organization and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

In his efforts to convince Than Shwe of the need for greater openness, Khin Nyunt often turned to the senior leader’s deputy, Kyaw Win, for help.

Kyaw Win was a specialist in psychological warfare who had served under Than Shwe since he was a junior officer in the army. It was known that he could freely enter Than Shwe’s office at any time. He often came late at night, offering tea or a massage, to talk about the need to allow more international agencies to operate in Burma and to tackle sensitive issues such as forced labor and the recruitment of child soldiers.

But it wasn’t easy. Than Shwe was stubborn and completely indifferent to the opinions of his foreign critics, said Aung Lynn Htut, who had met the top general on a number of occasions.

“He was a bulldog,” recalled the former major. “He didn’t really care about international pressure.”

On the child soldier issue, for instance, Than Shwe completely dismissed criticism, telling his subordinates, “Don’t worry. In two or three years, these kids will be adults.”

“He didn’t understand that this was a serious issue which we had to deal with at the UN,” said Aung Lynn Htut.

People who have worked with Than Shwe said that he is slow to make up his mind and rarely gives clear yes or no answers to questions, forcing officers to carefully decode his vague replies.

But if Than Shwe often seemed indecisive, he also had very definite ideas about what really mattered as far as world opinion was concerned. To his mind, the regime had no reason to worry about international pressure as long as Burma could maintain good relations with China, India and Russia.

What about the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean)? Aung Lynn Htut said that the senior general didn’t even take the regional grouping into consideration.

Even Thailand—the largest source of foreign investment in the Burmese economy—was powerless to influence the regime. Indeed, Than Shwe always insisted that Thailand’s dependence on Burmese gas and border trade gave the junta significant sway over Thai politicians.

But Than Shwe was not as complacent about other potential challenges to his hold on power. While the intelligence camp was making real headway with its overseas PR offensive, hardliners close to Than Shwe were growing increasingly wary of the influence of two people at home—Suu Kyi and Khin Nyunt.

Suu Kyi was considered the greater immediate threat. Her travels around the country had attracted huge crowds of supporters. The hardliners decided to strike back with a vicious attack on the pro-democracy leader’s entourage as they traveled near Depayin in May 2003. Suu Kyi was arrested and detained soon after the massacre, which claimed the lives of dozens of her followers.

According to Aung Lynn Htut, the intelligence unit, which had been tailing Suu Kyi’s motorcade around the country, had no forewarning of the attack.

“We knew they were planning something, but we didn’t know the real plan,” he said.

Suddenly, all of the regime’s PR gains were erased. The Bush administration stepped up its pressure on the junta and imposed tough new sanctions.

But Than Shwe wasn’t finished. Next he turned his attention to Khin Nyunt.

The senior leader was not alone in his mistrust of the intelligence chief. Vice Snr-Gen Maung Aye, the army chief, also saw a need to contain Khin Nyunt.

Than Shwe didn’t confront Khin Nyunt directly, but made some surprise moves at the Defense Ministry to undermine his influence. Most importantly, he brought in a few new faces: Gen Shwe Mann, Gen Soe Win, Gen Myint Swe and Gen Ye Myint.

Shwe Mann was being groomed to take over the commander in chief position and Soe Win was to take charge of the intelligence department. Khin Nyunt suddenly felt the heat. He was now accused of underestimating the potential threat of “the enemy”—Aung San Suu Kyi.

For the first time since 2001, when Than Shwe placed Khin Nyunt’s mentor, former dictator Ne Win, under house arrest after his daughter and grandson were accused of plotting a coup, Khin Nyunt found himself precariously close to becoming yesterday’s man.

Than Shwe’s next move was to name Khin Nyunt prime minister. According to former military intelligence officers, both Than Shwe and Maung Aye then urged Khin Nyunt to hand over control of the OCMI to either Myint Swe or Ye Myint. Khin Nyunt refused.

News of the SPDC’s internal conflict began to leak to the foreign press through senior military intelligence officers. Foreign Minister Win Aung hinted to his Asean counterparts that there was a bitter power struggle among the top leadership.

According to Aung Lynn Htut, strong business and personal rivalries added to the political tensions. Khin Nyunt’s wife and her circle of friends used to refer to Than Shwe’s wife, Kyaing Kyaing, and her closest friends as the “uneducated wives club,” he said.

Corruption was another key issue. Cases were being built targeting the spy chief. Several of his subordinates were arrested in northern Burma on corruption charges. Khin Nyunt’s name was also implicated when the authorities seized a fishing boat in Mergui with 500 kg of heroin on board.

After returning from a trip to Singapore in September 2003, Khin Nyunt had a heated argument with Than Shwe at the Defense Ministry and offered to resign.

But Than Shwe told him he had a new assignment to offer him.

In October, Khin Nyunt called a secret meeting with his top intelligence officers and ordered them to provide documents as evidence of corruption against Than Shwe and top army leaders. Shwe Mann heard about the meeting and immediately informed Than Shwe.

On his way back from a trip to Mandalay, Khin Nyunt was arrested and charged with corruption and insubordination.

The regional commanders and army officers who believed that Khin Nyunt was building a state within a state hailed the purge. In fact, Than Shwe succeeded not only in consolidating his power base but also in gaining even more support within the armed forces.

“The army all hated us [the intelligence unit] because we had information about them, and even I, as a major, could reprimand a regional commander,” said Aung Lynn Htut.

The mission to win hearts and minds was over. Asean, China and Khin Nyunt’s allies in the West and the UN were disappointed to see the “moderate force” arrested and locked up.

Than Shwe did not want to release Suu Kyi, although secret negotiations between her and the regime were resumed just before the government revived its National Convention in December 2004. Suu Kyi, in a spirit of compromise, even sent a letter to Than Shwe to show that she bore no grudges over the Depayin ambush.

During these meetings, Suu Kyi and her party leaders agreed to return to the convention if the regime released her.

Aung Lynn Htut, who was still in Washington at this time, received daily phone calls from Rangoon. He was told that it was almost 95 percent certain that the NLD was going back to the convention. At the last minute, however, the deal fell through. Than Shwe did not keep his promise to free the iconic pro-democracy leader.

Ironically, it was Khin Nyunt who had announced, in August 2003, that the National Convention would be resumed as part of a seven-step “road map” to “disciplined democracy.” Now, however, he and his family were under house arrest, and most of his closest subordinates—with the notable exceptions of Kyaw Win and Kyaw Thein—were serving long prison sentences.

Four years after the removal of Khin Nyunt and his entire secret police department, many in the armed forces still believe that he had a plan to stage a coup against Than Shwe and wanted to become commander in chief of the armed forces.

For Aung Lynn Htut, his former boss’s downfall spelled the end of his career in military intelligence. In March 2005, he sought asylum in the US.

Since then, he has been an outspoken critic of Than Shwe. Through overseas Burmese radio stations, he has called on the junta leader to step down and urged soldiers to remove him from power.

Aung Lynn Htut said he believed that many senior intelligence officers who are now in prison felt the same way.

Referring to the pro-democracy movement, he said, “We wanted to see the revolution succeed.”

No comments:

Post a Comment